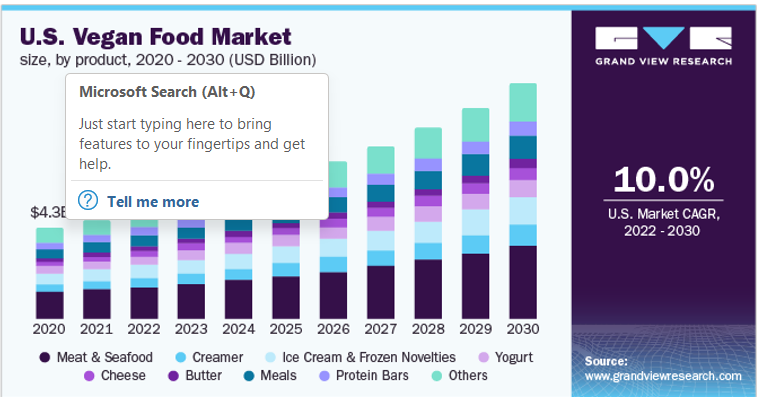

Vegan supply chains should recognize the need to authenticate their inventories in the restaurant businesses and the industry at large. In one recent supply chain challenge, the FDA raised the issue of tracking the origin of sources for vegan food, especially with the rapid growth of new entrants in the market (Banker, 2021), and rightfully so.

Nowadays, organizations are keen on vetting upstream and downstream supply chain sources to ensure that the vegan food we consume isn’t laced with animal products, the need to identify animal foods purporting to be vegan and being sensitive to food contamination by animal-based products.

Since veganism is in the best interest of not only animals but people and the planet, supply chains are also helping their sustainability efforts when attention is given to emerging vegan chains. This makes it even more important to not ignore this fast-growing lifestyle.

But the job of determining if your supply chain is truly ‘veganized’, comes at a time when supply chains have other major issues that they have not yet completely addressed, like modern-day slavery, avoiding conflict goods, debt bondage, child labour, and the list goes on. Still, these issues are all people-related issues that veganism also seeks to protect.

The UK Vegan society personifies this through its objectives and concerns, defining a vegan as someone who avoids the exploitation of animals for the benefit of animals, people, and the planet (Greenebaum, 2012)

The problems lie in traceability and transparency for traditional chains which vegan supply chains are not immune to. Traceability concerns have attracted a proliferation of laws, relating to the policing of conflict minerals (Dodd-Frank, Act), forced labour concerns being addressed by the Australian and UK modern slavery Acts, the California Transparency in Supply Chain Act along with additional legislation on its way in Netherlands and Switzerland (Bateman and Bonanni, 2019). And then there are the transparency concerns.

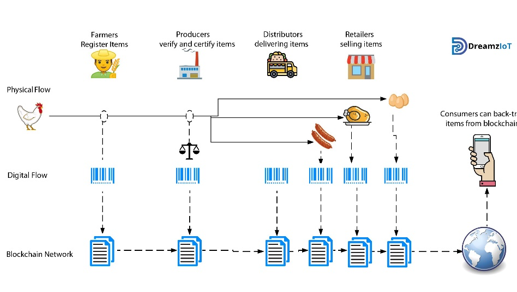

This relates to the extent to which stakeholders have shared their knowledge and understanding as well as access to information, without noise, delay, or any kind of distortion (Hofstedel, 2005; Deimel et al., 2008). A huge feat for supply chains to achieve but by no means impossible. One way forward is technology, but trusted technology, that informs all nods or to put it simply, suppliers, buyers, and consumers on what information is being shared.

This is where blockchains do well, with data being viewed openly and held to account by everyone who sees it. Admittedly, these solutions might be light years away from some upstream providers who may not be able to access the technology now, much less meet the criteria required to be part of the blockchain ecosystem.

While blockchain technology remains a costly venture and the development is ongoing, what supply chains must continue to do is drive awareness for supply chain scrutiny within the vegan community, adopting Aung and Chang, (2014), definition of traceability that sought to focus on the ‘where’, ‘why’, ‘what’ and ‘when’.

Bibliography

1. Aung and Chang, (2014) ‘A Framework for Traceability and Transparency in the Dairy Supply Chain’ ScienceDirect

2. Banker (2021) ‘Sustainability And Plant-Based Meat Supply Chains’, Forbes

3. Bateman and Bonanni, (2019).‘What Supply Chain Transparency Really Means’, Harvard Business Review

4. Grand View Research-Vegan Food Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report

5. Greenebaum, (2012), ‘Veganism, Identity and the quest for Identity’ Food Culture and Society

6. Hofstedel, (2005) ‘A Framework for Traceability and Transparency in the Dairy Supply Chain’ ScienceDirect

7. Processed Food Industry – FSSI notifies final vegan foods regulations 2022